(This is a continuation of a post I made in 2010 about this issue. This analysis based on the 2013 Alternative Resources in Media dataset.)

So, the social networking site that one spends time on isn’t arbitrary. Research tells us that generally people go where their friends are, but also that there are demographic differences in site choice. A study of MySpace versus Facebook in 2007 is the classic case of this. For a variety of reasons, wealthier and more educated people were on Facebook and poorer and less educated people were on MySpace. Nowadays in the U.S., Facebook has sort of taken over the social networking space and a lot of those demographic differences have gone away.

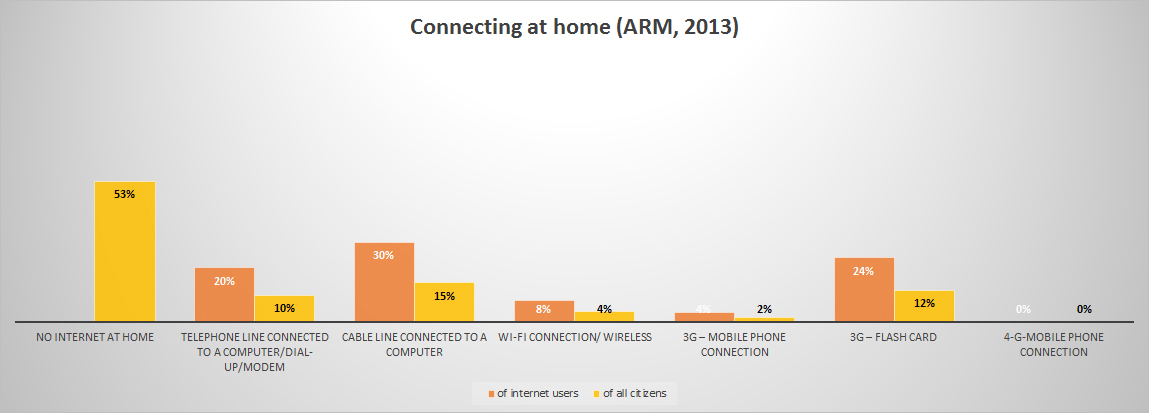

In the 2010 analysis posted above, Facebook in Armenia was quite elite while Odnoklassniki was not. Some reasons include that Odnoklassniki was more accessible on for free or cheap on mobile devices, the Russian language interface was more accessible to those without English skills (at the time Facebook was mainly an English language platform), Odnoklassniki was more about fun (and porn), and Facebook wasn’t great on a mobile device.

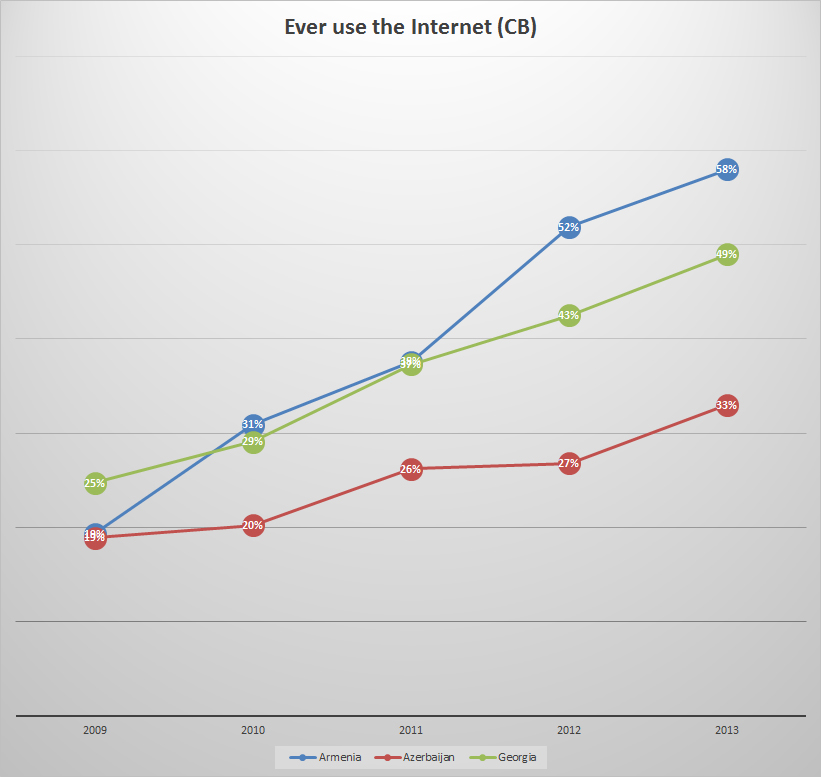

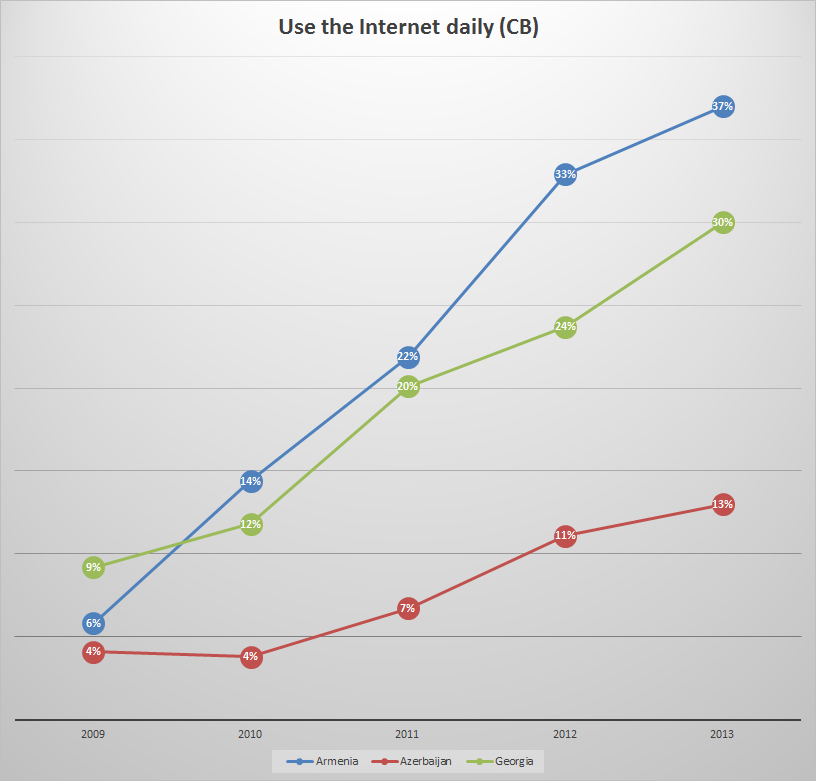

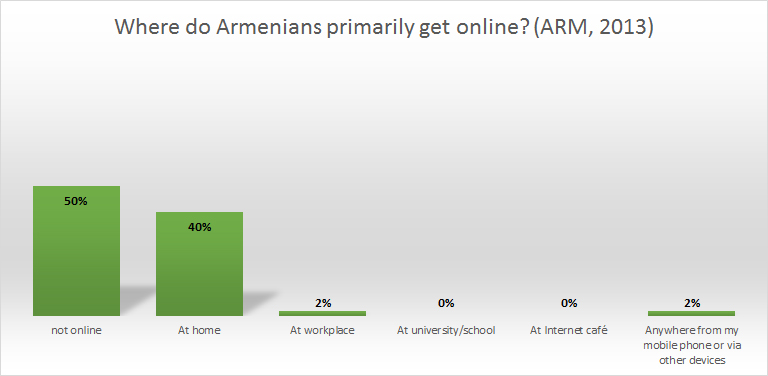

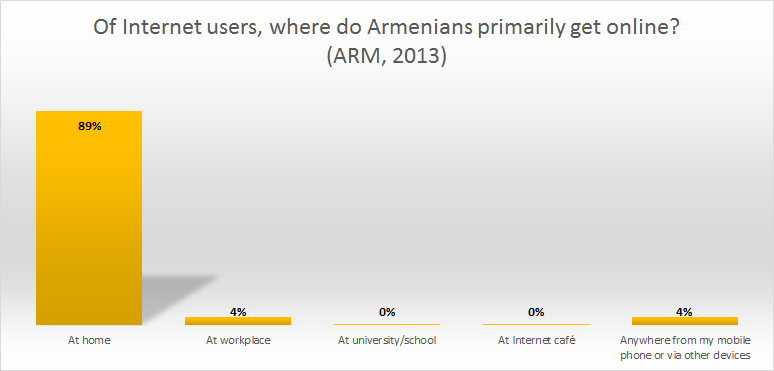

Fast forward to 2013, and things have changed. Facebook has grown a lot globally. The Facebook mobile platform is very user-friendly. Russian and Armenian versions of Facebook work quite well. More Armenians are online as well.

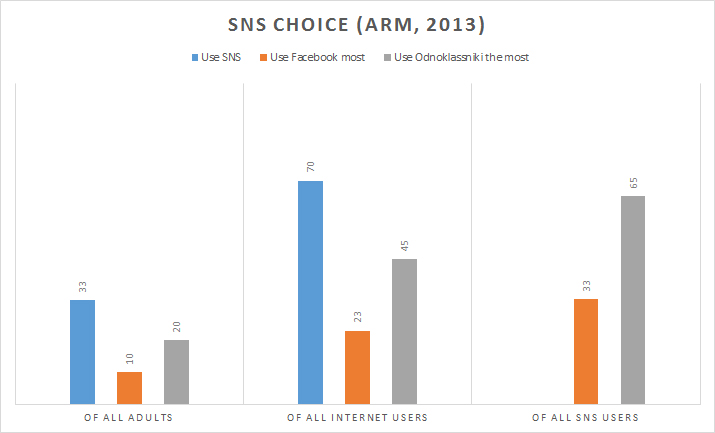

So I looked once again at use. Let’s first look at the overall picture before going into the demographic differences.

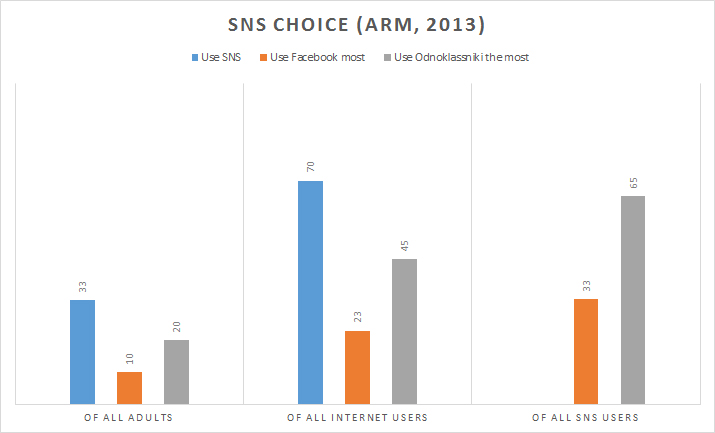

(Note that this is PRIMARY SNS, they could have accounts on the other site.)

First you can see that a third of all Armenian adults are on a social networking site and 70% of all adult Armenian Internet users are on a social networking site. The Odnoklassniki versus Facebook breakdown is that 10% of all Armenian adults are on Facebook, but 20% of all Armenian adults are on Odnoklassniki. Of Internet users, less than a quarter are on Facebook while nearly half (45%) are on Odnoklassniki. The comparative breakdown is a third of SNS users on Facebook and two-thirds on Odnoklassniki.

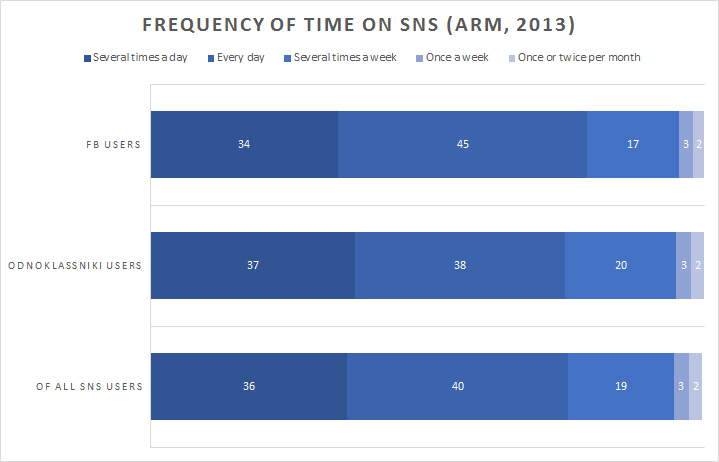

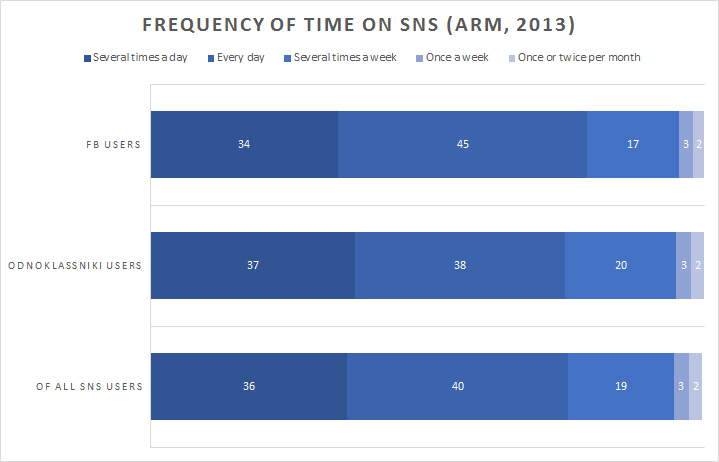

In terms of the time that is spent on the social networking site, there weren’t tremendous differences. About a third are on the SNS several times a day and most of the rest of the users are on the SNS at least once a day.

So who is on each site?

(This is based on an ANOVA):

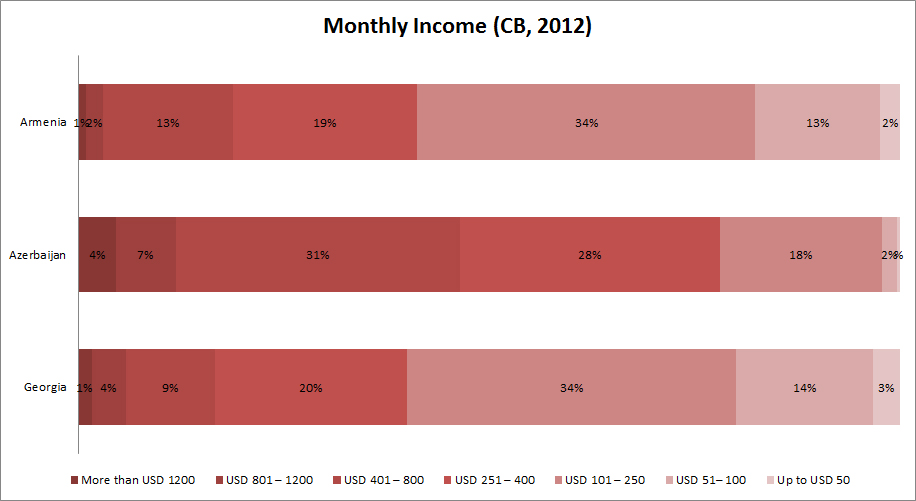

There is no difference in age between Facebook and Odnoklassniki and other SNS users in AGE. However, non SNS users are much older. It is the same story with ECONOMIC WELLBEING – non SNS users are poorer than SNS users. The same is for RUSSIAN skills – the only difference is with non-SNS users and users.

ENGLISH skills – Facebook users (and other SNS users, but they’re weird, so let’s ignore them) have statistically significantly higher English skills than others.

Facebook users are also statistically significantly higher in EDUCATION than everyone else.

No differences in SEX.

So, we can summarize that Facebook users are more elite – English speaking and better educated. Thus, not a big chance from 2010.

(This is based on a multinominal logistic regression):

Looking at this 2013 data, the determinants of being an Odnoklassniki user are the following. In this analysis, all the different factors consider each other, so for example, the influence of higher education on English language skill is cancelled out, so each variable is really telling its own story.

First, Sex – men are more likely to be on Odnoklassniki than women. Next, Russian language skills – those with better Russian are more likely to be on Odnoklassniki than those with poor Russian. Then English skills matter. Then education.

Determinants of being on Facebook are first English skill. Better English means more likely to be on Facebook. Next, higher education. Russian language skill matters next.

For both Odnoklassniki and Facebook, age and economic status didn’t matter much. However, younger and wealthier people are more likely to be online. So it appears that once you’re online, your choice of social networking site is more about language skills and education.

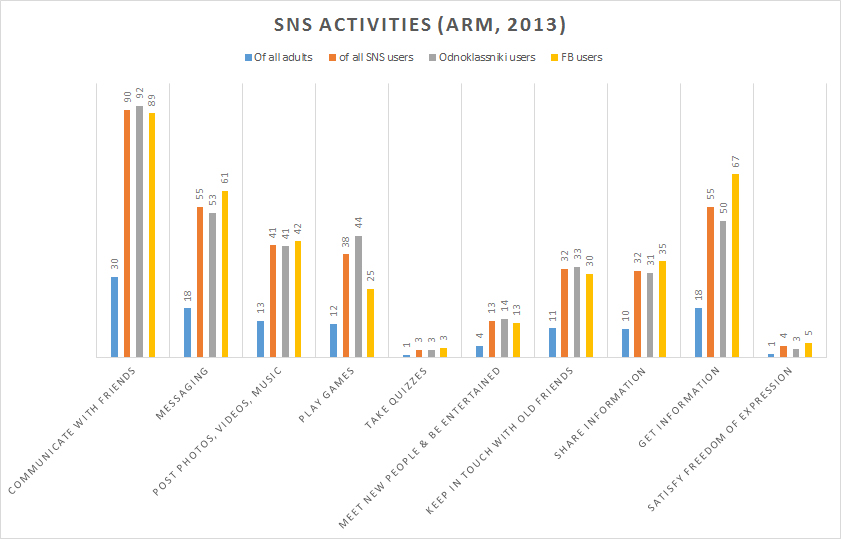

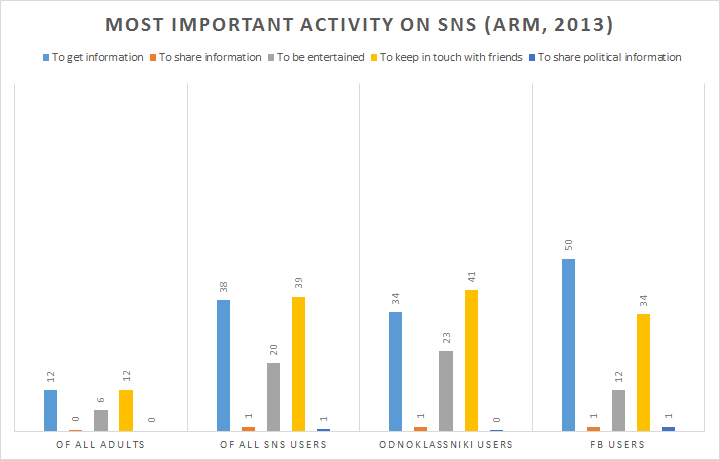

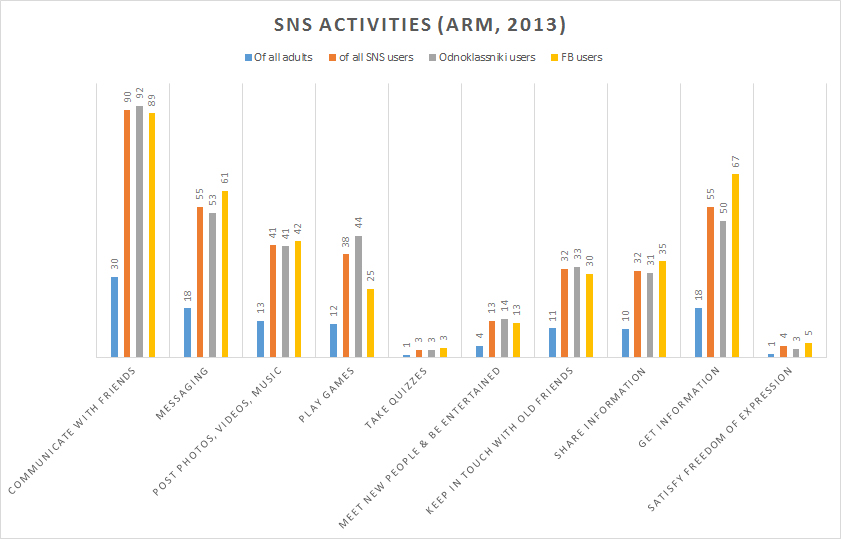

So, with that, what are people doing on social networking sites?

Remember that Facebook users are more “elite” – so the activities they do will likely be more elite as well.

In terms of communicating with friends, posting photos, and entertainment no big differences between the sites. However, Facebook users are more interested in getting and sharing information. Odnoklassniki users are also playing more games than Facebook users.

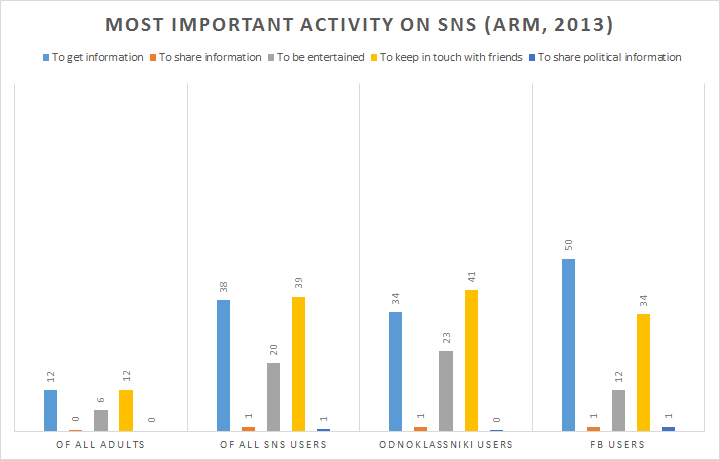

When asked what the most important activity on a social networking site, Facebook users were much more likely to say getting information.

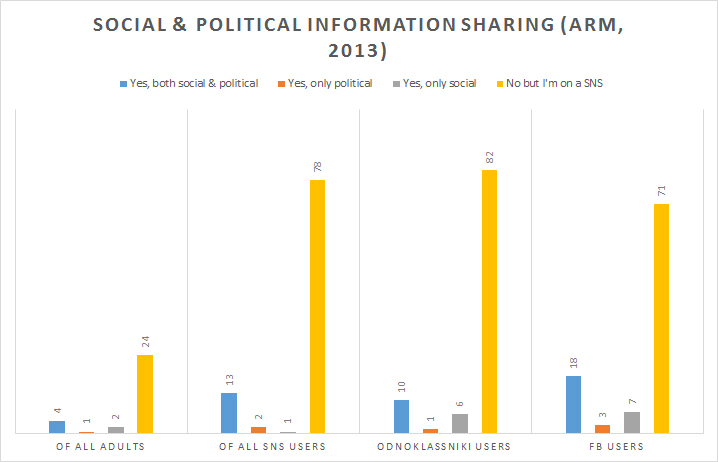

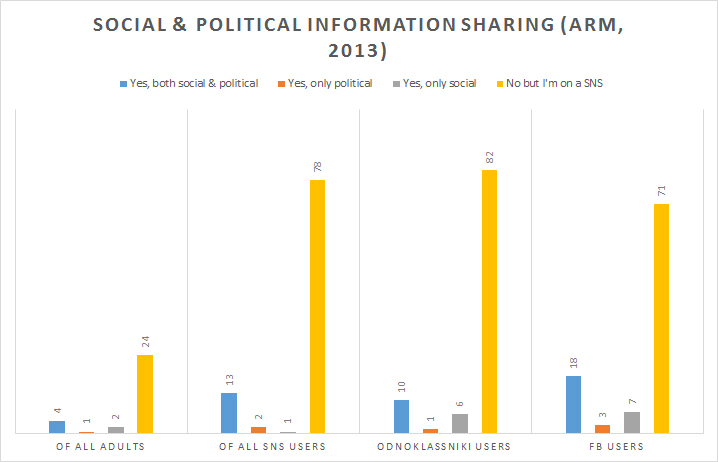

When asked about sharing political and social information, Facebook users are much more likely to share than Odnoklassniki users. But the majority of all social networking site users aren’t sharing (they say!).