Tag Archives: azerbaijan

Trust and Gender in the Caucasus

I wrote a blog post a few weeks ago about interpersonal trust (using EBRD data). One of my arguments is that Azerbaijanis have very low interpersonal trust. After a conversation with a girlfriend, I had the idea to look at gender differences in trust as well. This is with CRRC data.

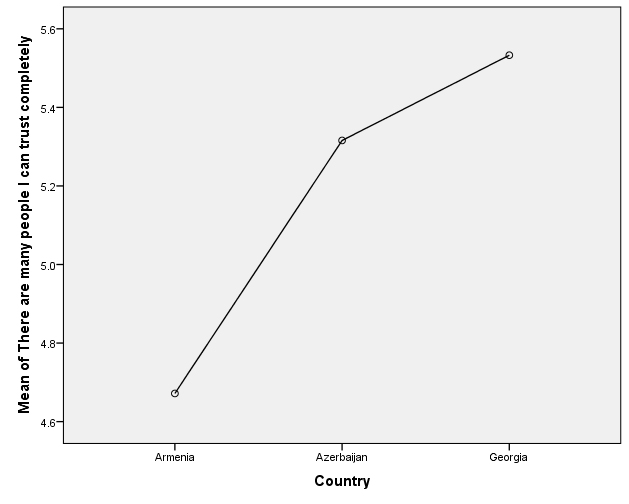

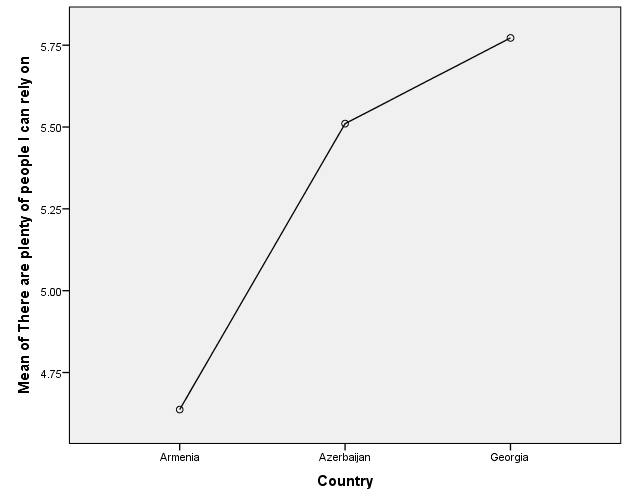

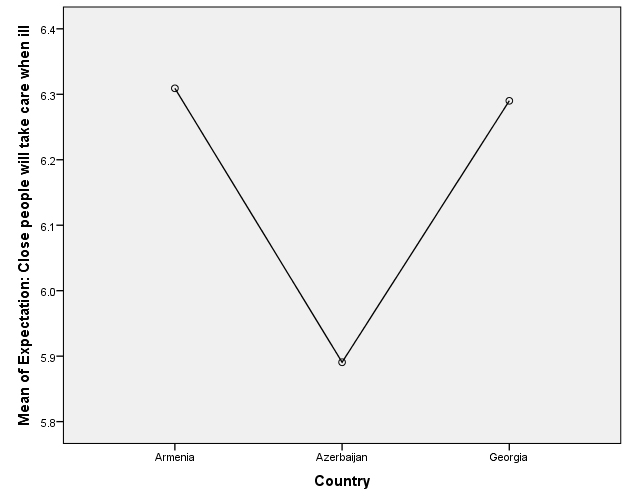

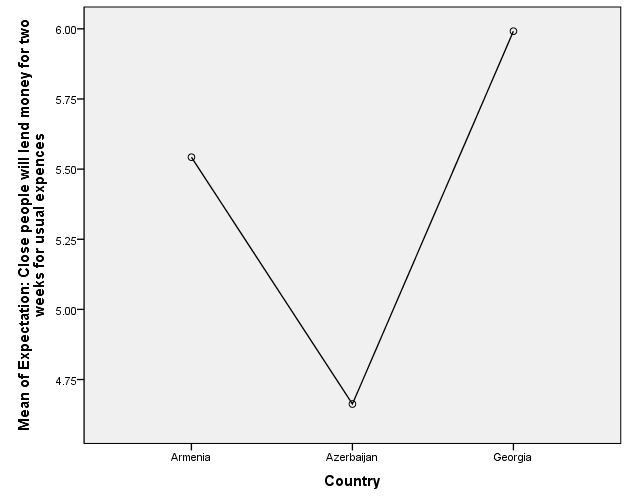

First, without gender, you can see that generally Azerbaijanis have much lower trust in others than Armenians or Georgians do, but this varies by question. (These are on a 1-10 scale with 1 not trust, 10 trust completely or 1 total disagree and 10 totally agree).

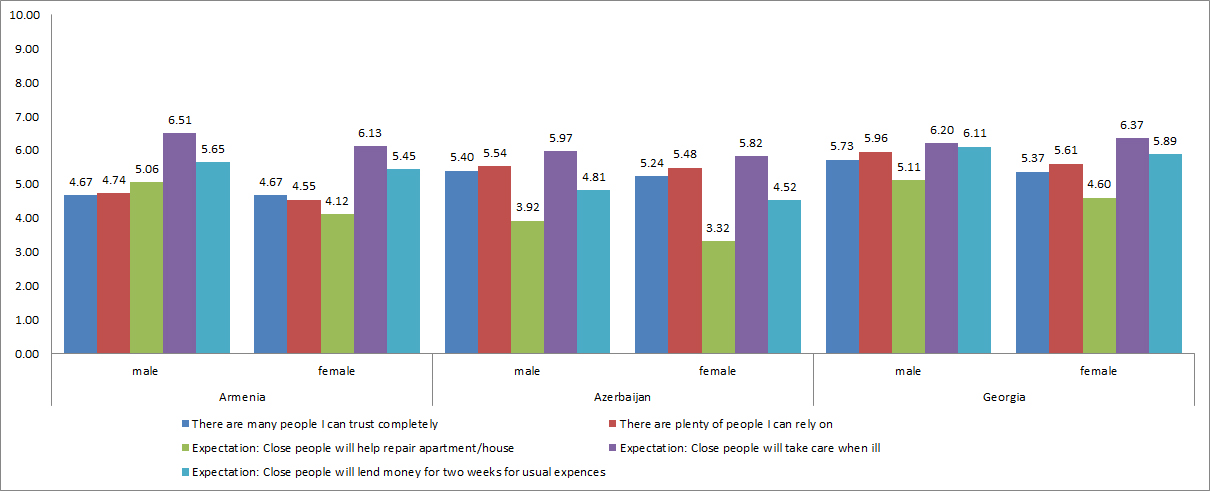

In this next chart with gender, you can see gender differences in a variety of questions related to interpersonal trust. The only time that there was no significant difference in trust between men and women is for Armenians with the question “there are many people I can trust completely” – otherwise all these differences are significant.

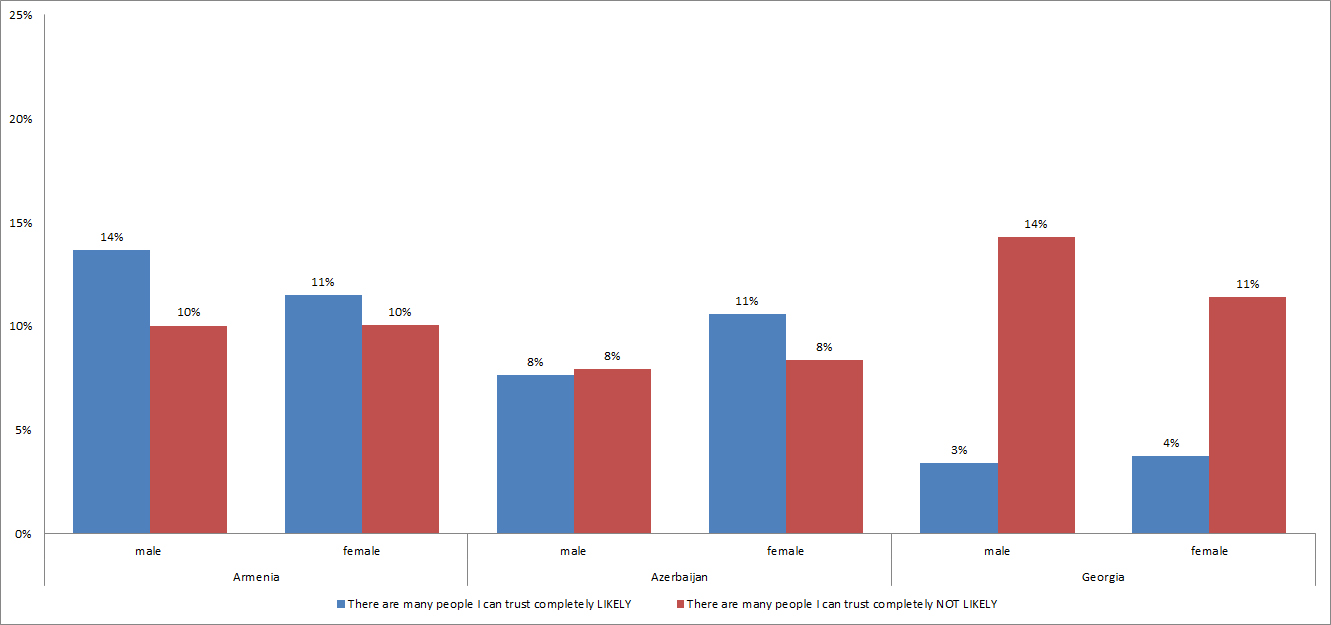

But looking at the two extremes – completely agree and completely disagree, things are also interesting…

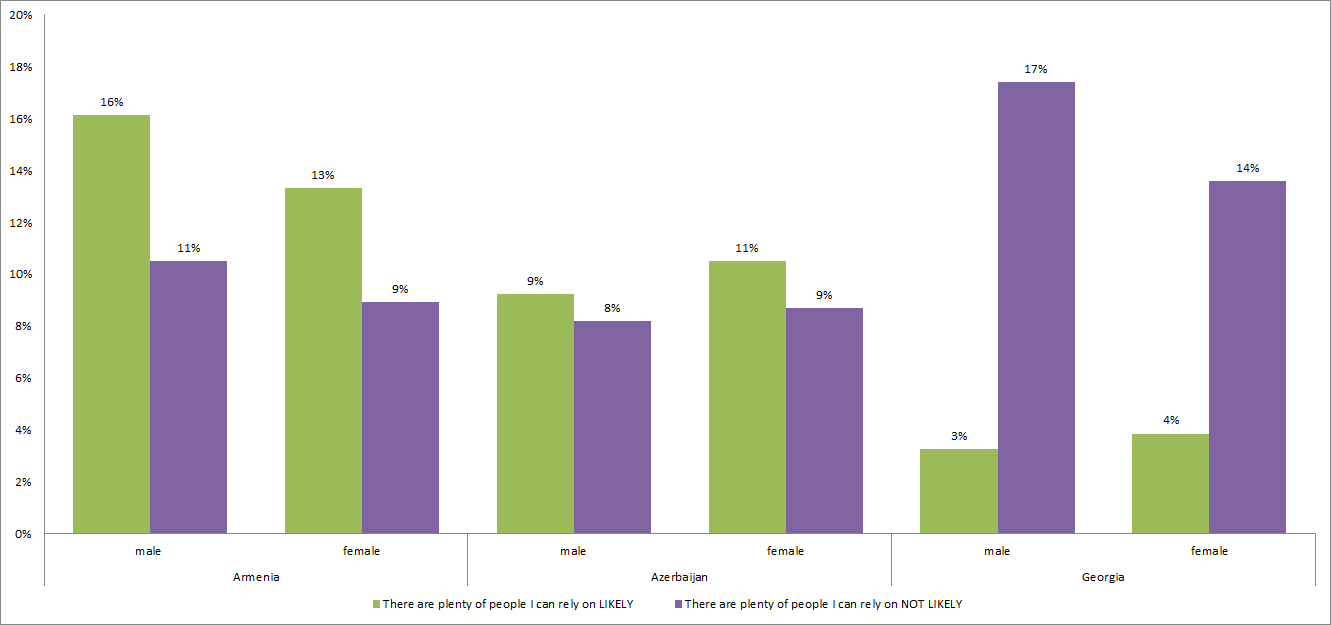

In this question of people that one can trust completely, Georgians seem to have it the worst, with only 3 or 4% having someone like that. Overall gender differences aren’t that stark in this question.

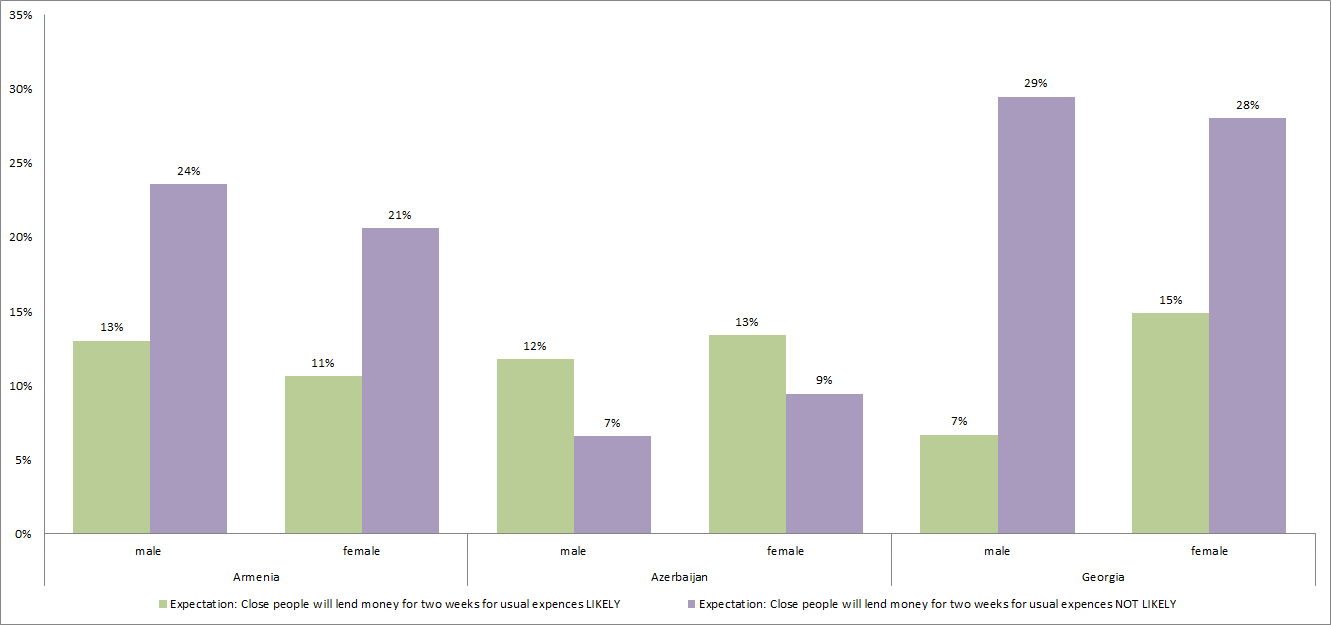

Here for money lending, big country differences. Georgians can’t get a break, huh? Gender differences here exist, but not too harshly.

For reliable people, Georgians again are in a bad spot.

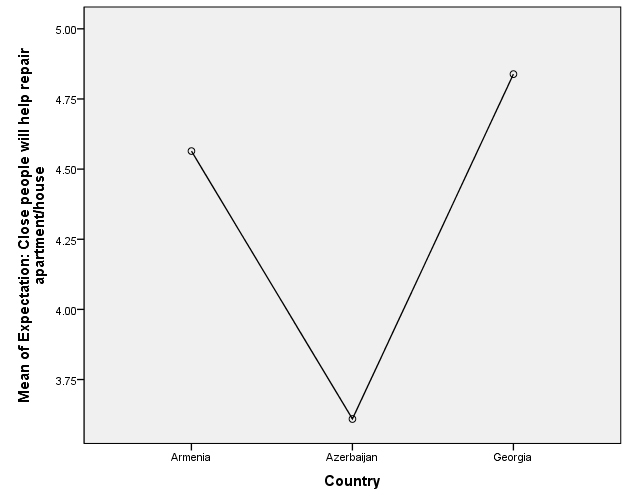

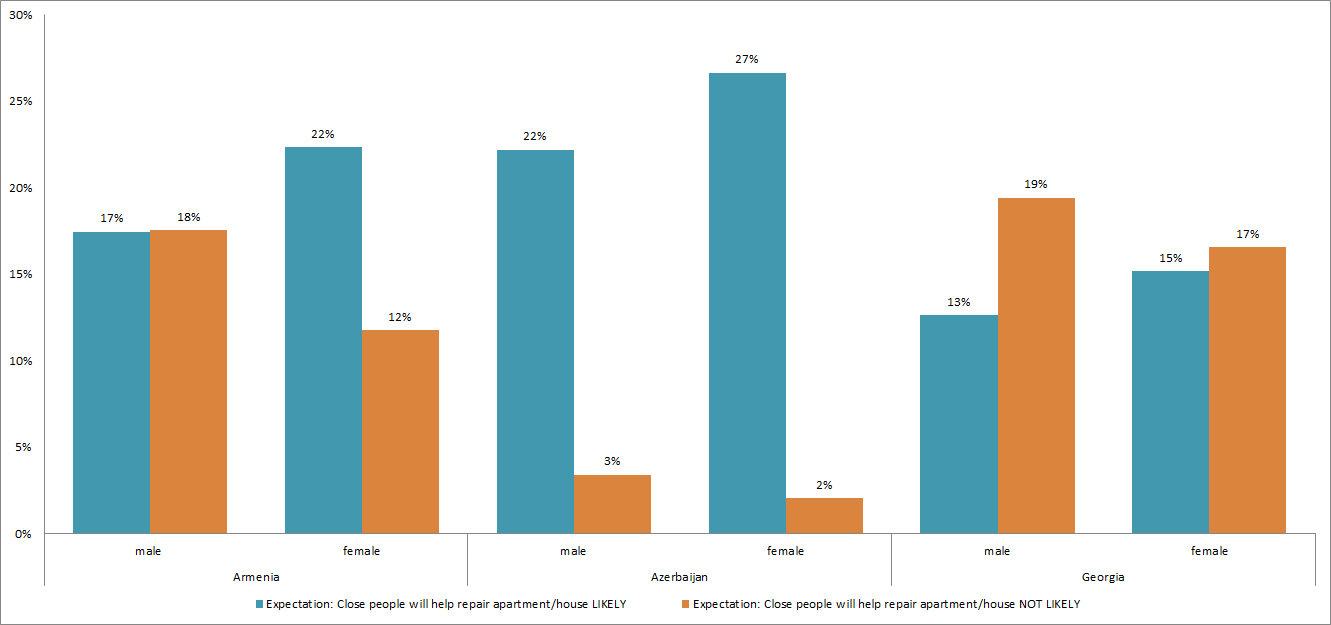

Help repair the apartment – well, this is a lot to ask of people, right? Georgians again are not doing well here.

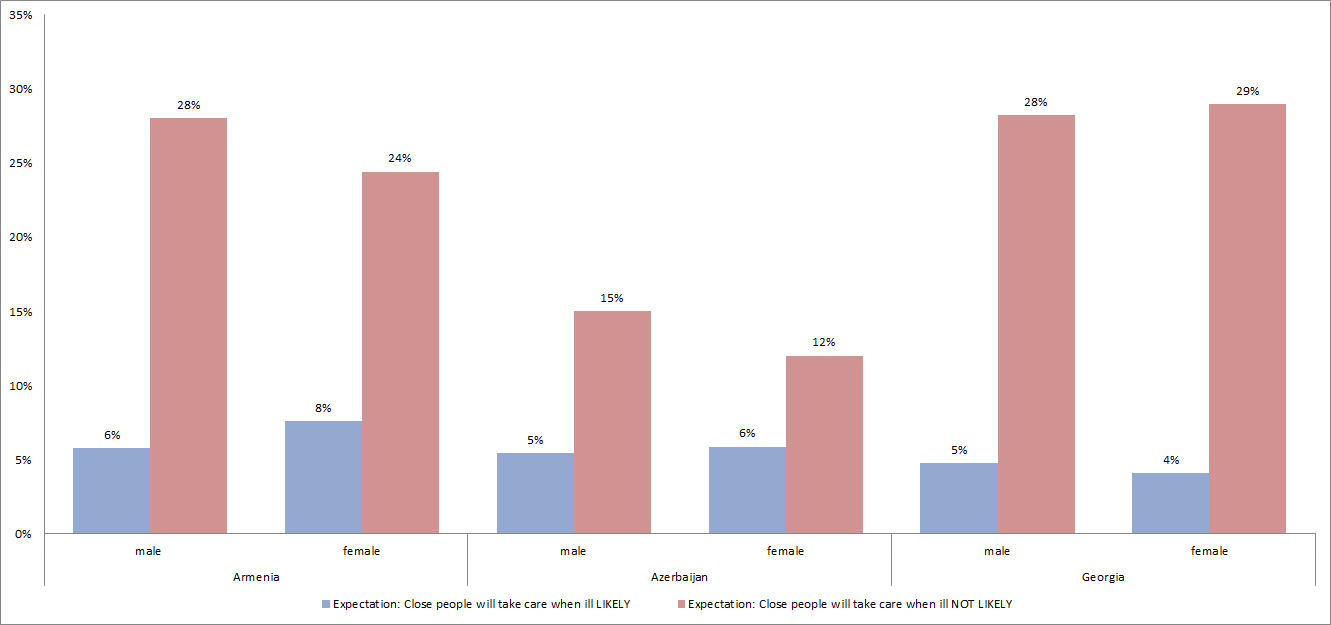

I don’t want to get sick in the Caucasus. Looks like people have trouble finding people to help care for them. Again, no major gender differences here.

So overall, despite there being a statistically significant difference in trust between genders, it doesn’t really manifest in these practical questions.

Material Deprivation in 2012

A few years ago I wrote a piece about measuring poverty in the South Caucasus.

That paper ended with 2010, but I was talking about it with someone yesterday, so I did some quick 2012 updates.

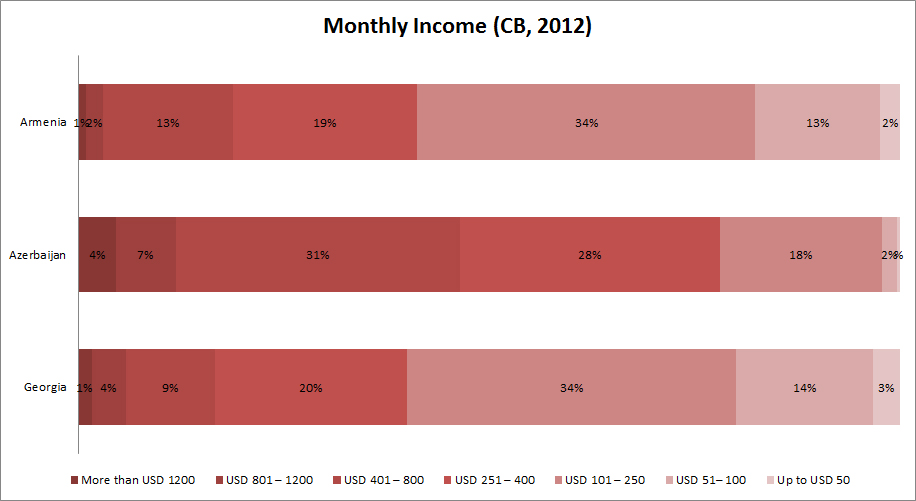

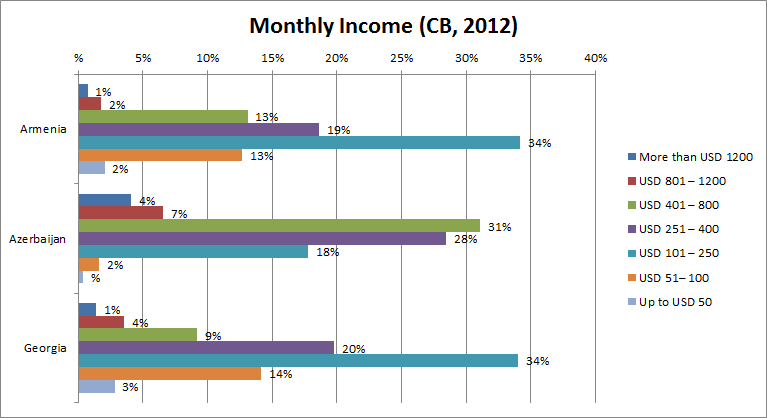

As far as monthly household income in 2012, the distribution hasn’t changed much since that 2010 paper, but you can see that Armenians and Azerbaijanis are doing much better economically.

In the paper I argue that material deprivation is the best measure of economic wellbeing because it reflects household ability to buy consumer goods.

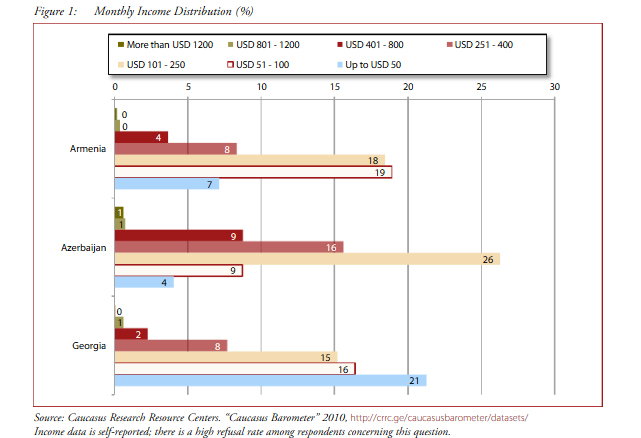

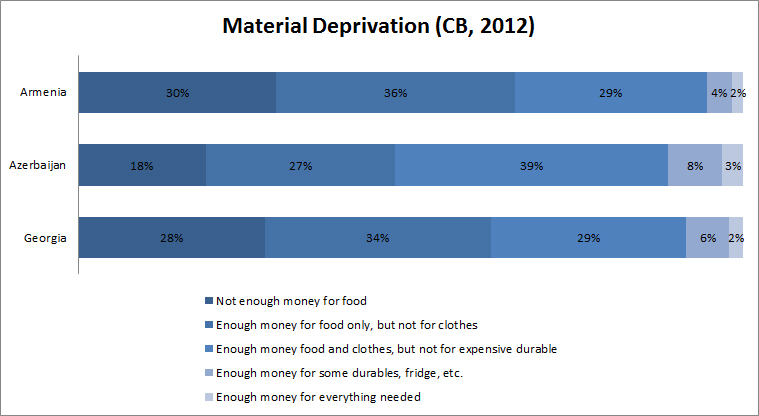

This is the 2009-2010 distribution of material deprivation:

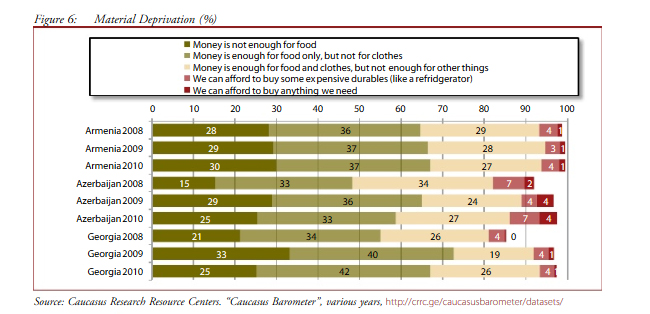

And this is the 2012 update.

Armenia didn’t change much. Azerbaijan has less people at the poverty end of the scale, so that’s a positive change. Georgia had a bit of a change in more people in the enough for food category, but about the same in poorest category.

It is hard to see economic changes in such a short period of time – it would certainly be worthwhile to do some trend analysis here. Maybe next year!

Attitudes toward IDPs in Azerbaijan

Sometimes sitting around in a coffeeshop brings interesting ideas. While sitting with Jale Sultanli today, she speculated that IDPs in Azerbaijan hold different attitudes toward Karabakh than other Azerbaijanis. I, always the nerd, said LET’S TEST THIS!

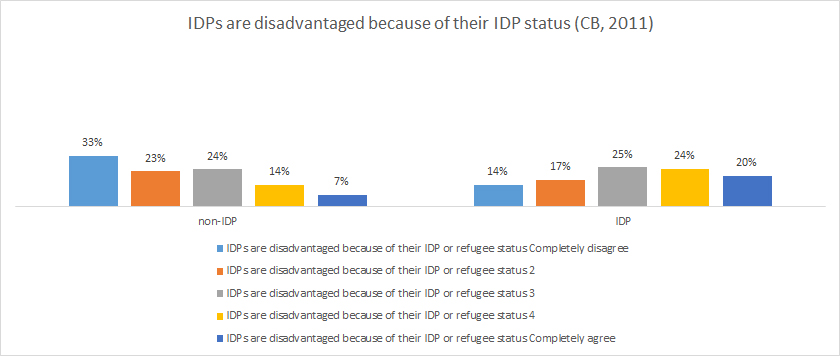

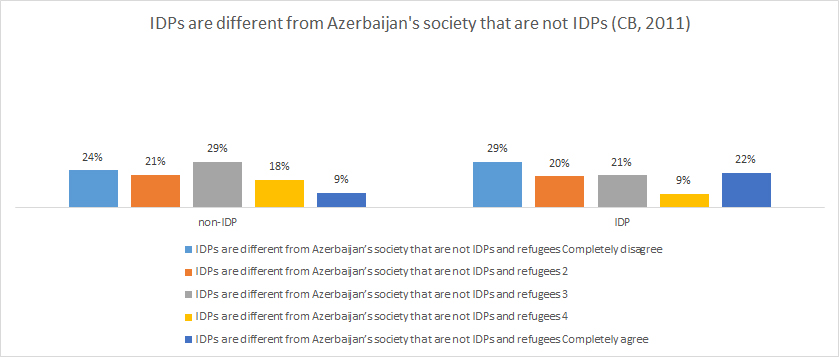

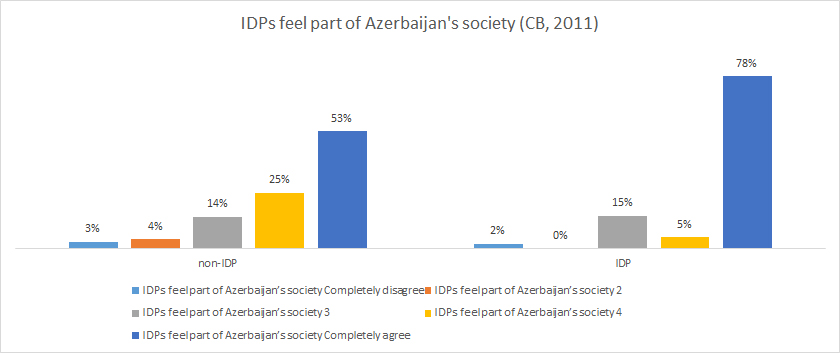

So we did a series of analyses comparing IDPs and non-IDPs. Here is the first set of attitudes – questions about IDPs’ role in society.

The first issue is – are IDPs disadvantaged. Unsurprisingly, IDPs believe they are more disadvantaged than non-IDPs believe they are. A third of non-IDPs think that IDPs are not disadvantaged at all.

But are IDPs different from other Azerbaijanis? This is more of a mixed bag. (And perhaps an odd question.) IDPs are mixed – 22% say they are completely different and 29% say not different at all. While most non-IDPs (29%) are in the middle on this.

So, do IDPs feel that they are a part of Azerbaijan’s society? The IDPs themselves sure think so! Over three-quarters feel that they are completely part of the society. A little over half of non-IDPs believe so.

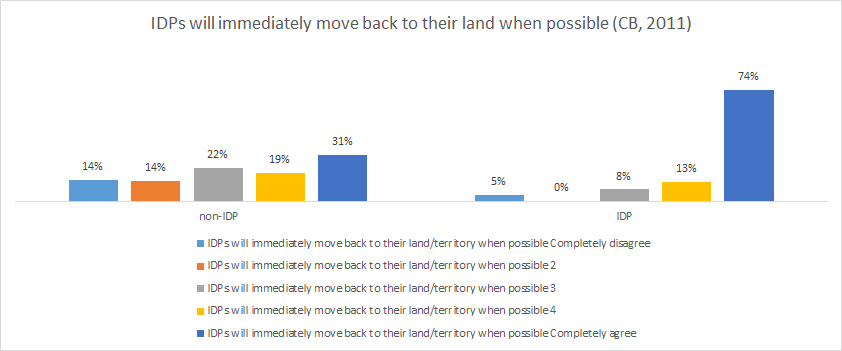

Jale told me that a lot of non-IDP Azerbaijanis think that IDPs don’t want to move back – they like their new digs more. However, according to this, this is just not true. Three-quarters of IDPs say they will immediately move back when possible. Whereas under a third of non-IDPs believe (completely) they the IDPs would move back.

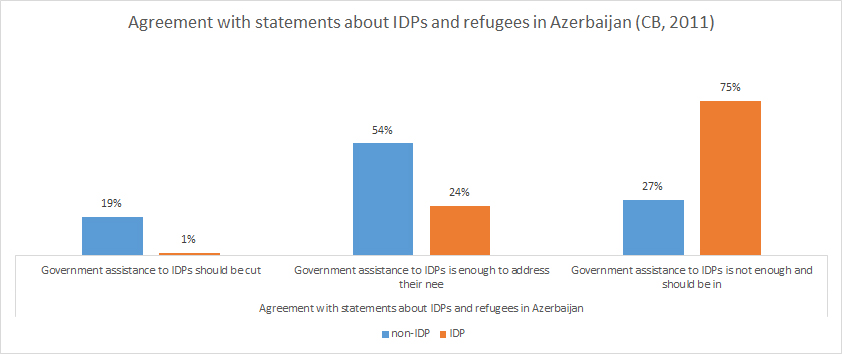

Some non-IDPs were unhappy (early on) that IDPs were coming to Baku, so there may be lingering concerns about the amount of support that the IDPs receive. Moreover, some Azerbaijanis feel that IDPs perhaps are taking advantage of the support they receive by not working. Unsurprisingly, three-quarters of IDPs feel that the government should be supporting them more. While a little over a quarter of non-IDPs feel this way. 19% of non-IDPs feel that the government assistance should be cut.

What does the Internet think of the South Caucasus?

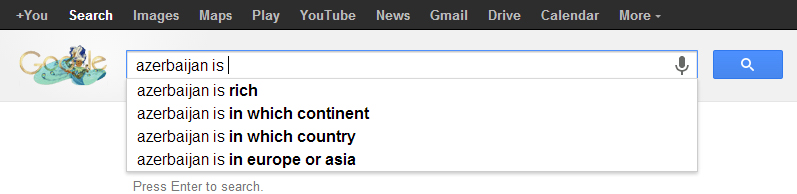

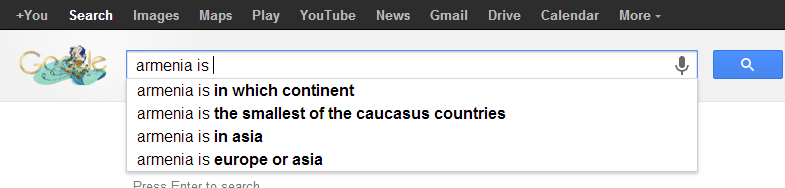

Well, really just Armenia and Azerbaijan… Googling for Georgia is too difficult.

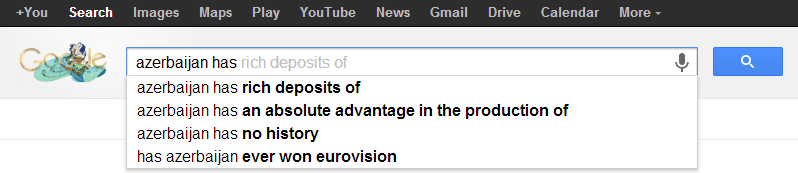

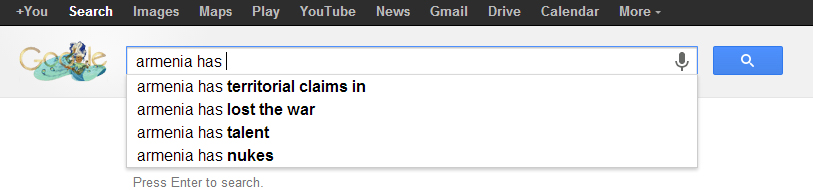

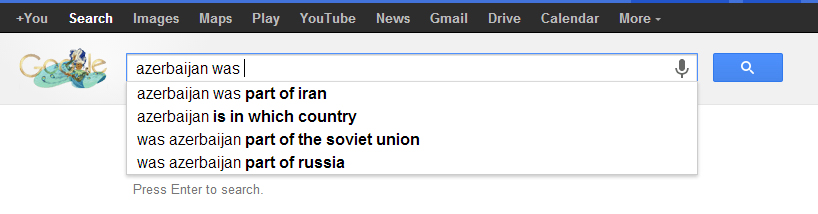

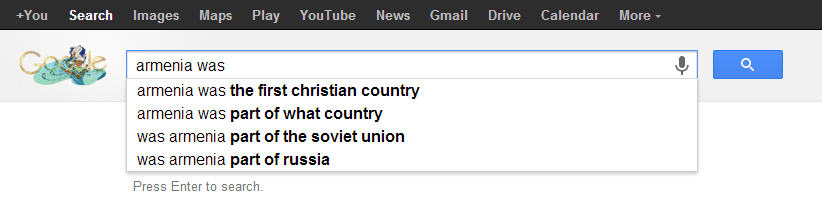

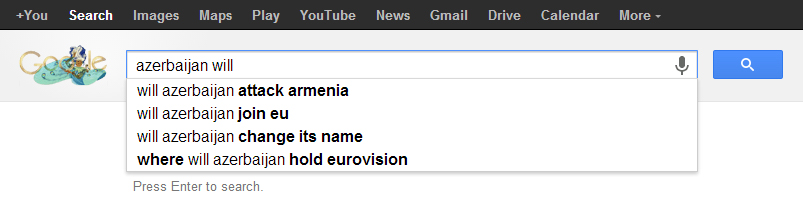

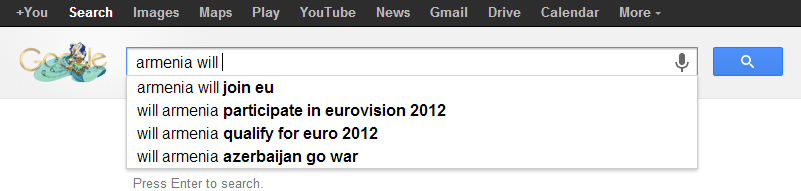

Inspired by this campaign that looked what Google automatically fills in for searches about men and women, I tried to do this with Armenia and Azerbaijan. I was logged out of Google, so these are the “natural” search results, not influenced by my own.

Yes, Azerbaijan is rich! And absolutely, the question of its position in Europe or Asia is an important one. Which country? Well, I guess with Southern Azerbaijan in Northern Iran, this could be a little confusing.

Again, the continent thing is really confusing. I don’t blame you for searching for this, users of Google.

Here is an interesting selection. No history? Impossible.

Armenia Has Talent! Awesome. And no nukes, sorry.

Excellent questions, Google users. Russia versus USSR is a tough one for you young people, I guess.

Yes- first Christian nation!

I ask two of these four questions often. Guess which ones?

I ask three of these four questions often. Guess which ones?

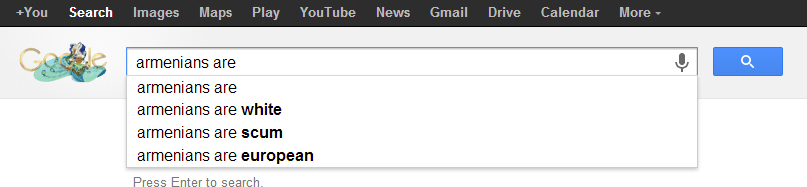

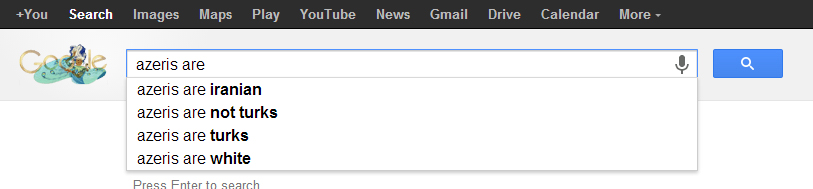

Well, some of these are not nice and some are interesting empirical questions.

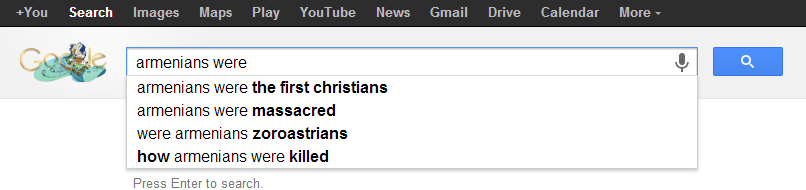

Interesting questions here too.

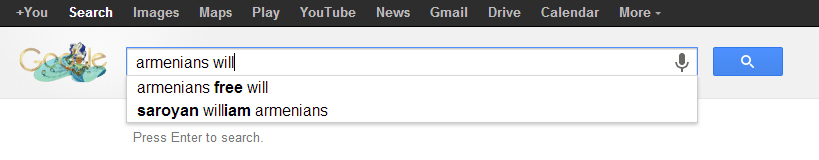

I love William Saroyan!

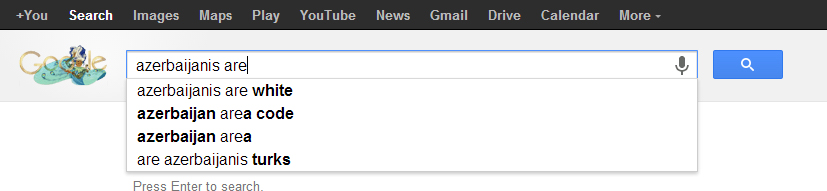

Area code and ethnicity – excellent questions.

Oh wow – this sums up a lot of the questions swirling in someone’s head.

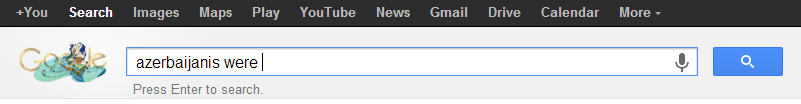

Weird that nothing came up for these.

_____________

So interesting stuff people of Google!

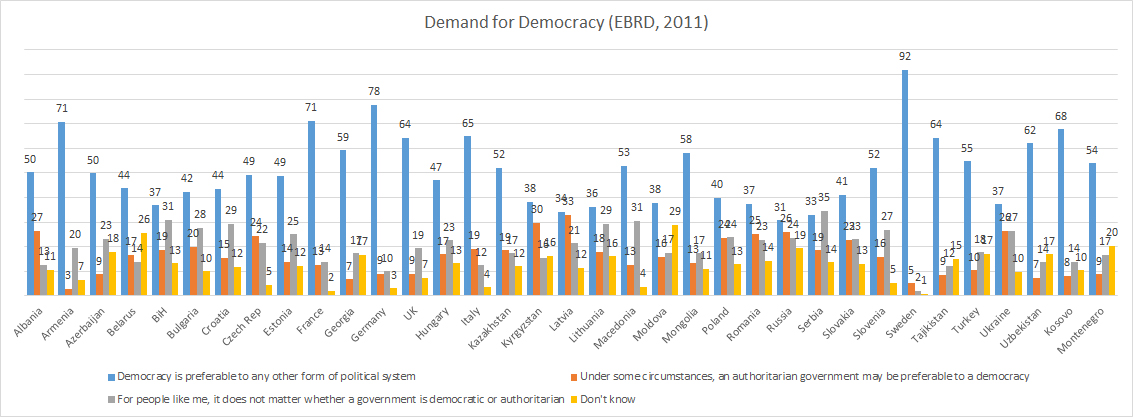

Demand for Democracy in Europe and Eurasia

Demand for democracy is one of my favorite outcome (dependent) variables. It isn’t perfect, but it is used frequently in public opinion surveys and has been shown to be correlated with all sorts of interesting things.

In a transitional society, popular demand for democracy (or legitimation) takes the form of a choice between competing regime types with which people have some degree of familiarity. Thus, survey questions should preferably not ask people how much they like democracy in the abstract (for example, through agreement or disagreement with one-sided Likert scale statements). Instead, they should offer respondents realistic choices between democracy and its alternatives.” (from here)

“Which of these three statements is closest to your own opinion? (A) Democracy is preferable to any other form of government; (B) In certain situations, a nondemocratic government can be preferable; or (C) To people like me, it doesn’t matter what form of government we have.”

A study that I did with Erik Nisbet and Elizabeth Stoycheff found that: Internet use, but not national Internet penetration, is associated with greater citizen commitment to democratic governance. Furthermore, greater democratization and Internet penetration moderates the relationship between Internet use and demand for democracy.

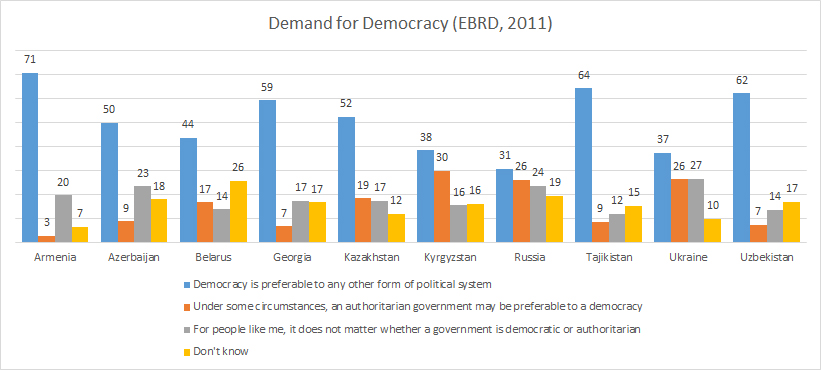

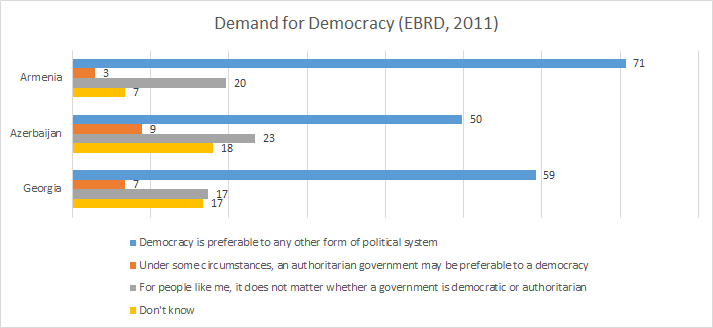

So, I was playing around with the EBRD Life in Transition II data today and did some graphics.

Wow, Swedes love democracy.

The variance in the former Soviet states is really interesting.

And then we have the Caucasus. Looks like Armenians LOVE democracy.

Only half of Azerbaijanis prefer democracy.

Pretty high don’t knows in Azerbaijan and Georgia.

Shenanagins again and again

I’ve written a lot about “winning” hashtags and how this is a boastful tool for organizations. Here’s what I wrote yesterday on it.

I’ve also written about trickery using Twitter. Here’s a good one.

But now I have a new story…

As I was going through the Azerbaijani election hashtags, I noticed something funny.

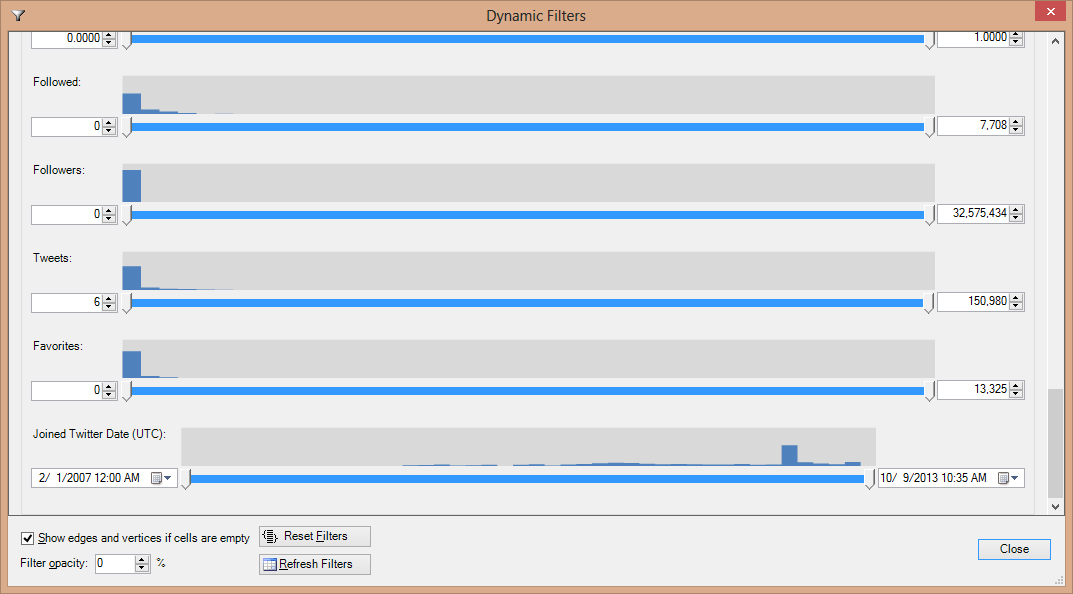

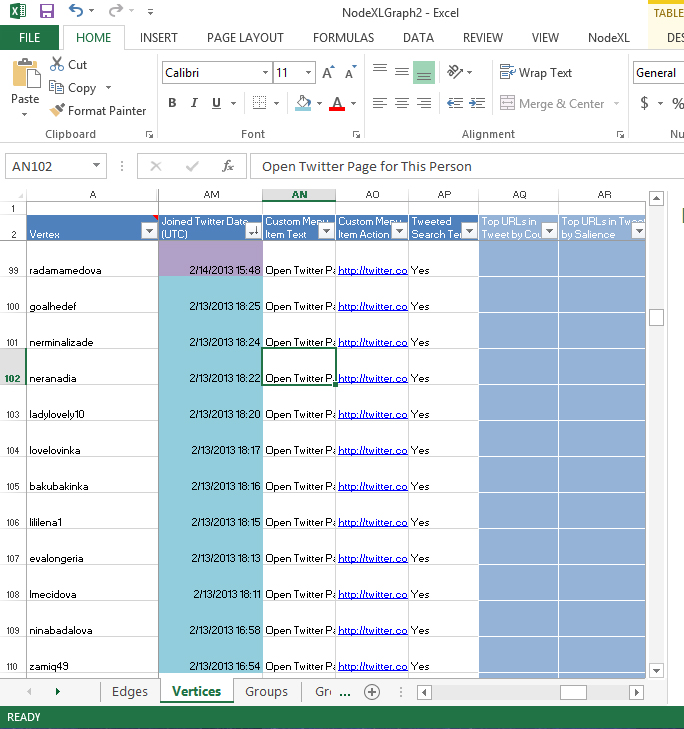

This is all the users that used the hashtag #azvote13 in the last day. Look at how many people opened a Twitter account on a few days in February of 2013.

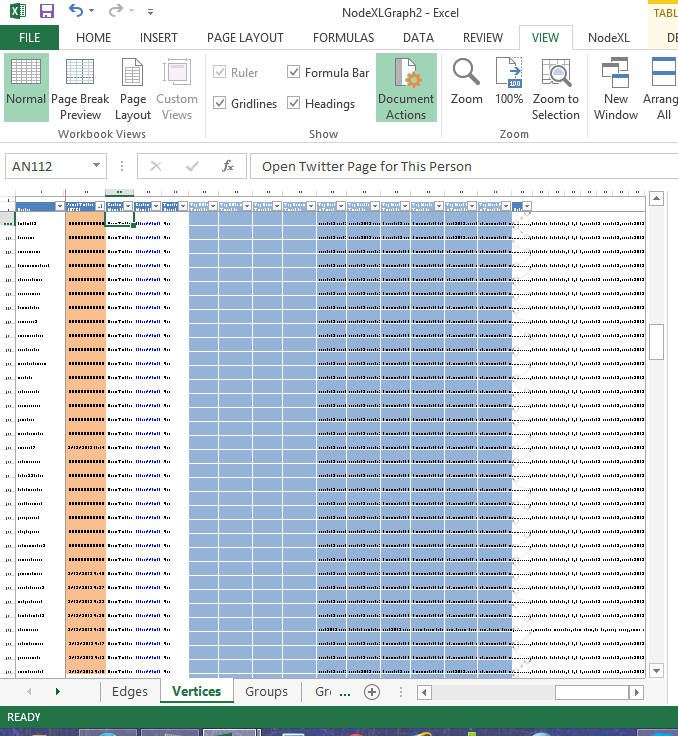

So I went to look at what was going on in those days in February. Not only were those accounts made on the same day, but they were made within minutes of each other. (If they’re highlighted the same color, it was the same day.)

So it is possible that there was some sort of training where a bunch of people created Twitter accounts at the same time, so I looked more closely at these accounts made in these days in February.

They generally follow the same few people. They generally don’t tweet a lot. Most haven’t tweeted a lot until this election period. I did a search on Facebook for some of them and no Facebook profile came up for them. It is possible that these young people spell their name differently on Twitter and Facebook – but in general I find that most young Azerbaijanis pick one way to spell their names on social media and stick with it.

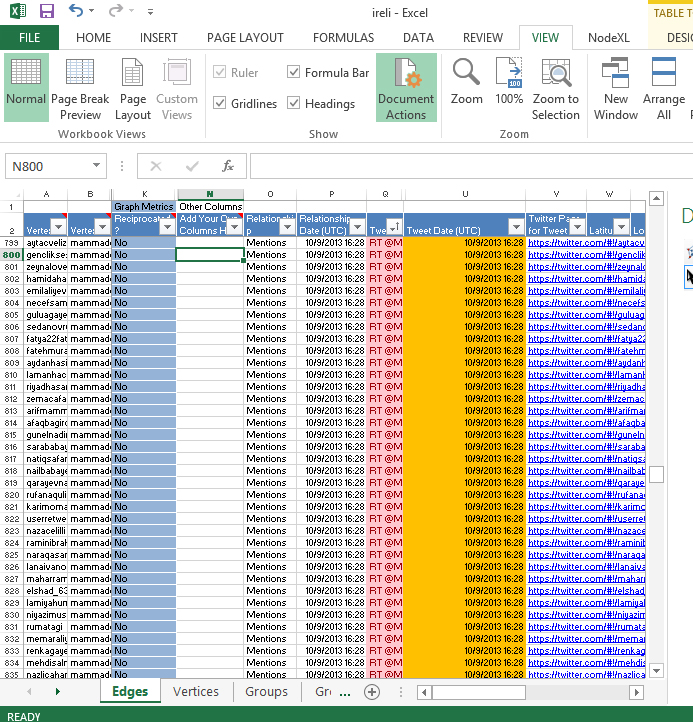

So what were they tweeting about on the #azvote13 hashtag?

The same thing. The red/pink tweets are duplicates and the orange highlight is the same time. And they are at the exact same minute.

While it is theoretically possible for tweets to happen at the same minute, 100 tweets at the same minute by accounts all made in the same few days within minutes of each other? That’s a stretch.

What is interesting about this:

– this is way less detectible than buying fake Twitter accounts because the names are Azerbaijani, the profile pictures look like Azerbaijani people, even though there isn’t a lot of evidence that they are real.

– it is entirely possible that these are real people, but regardless, I speculate that one person has all the passwords and probably uses a particular app to send out the tweets at the same time.

– UPDATE 10PM BAKU TIME: I did a quick reverse image search on some of the profile photos of some of the profiles. The photos are ones that people can download and use all over the place. Here are some links and PDFs 1 2 3. And here are the original profiles.

– so, nice try – this was certainly more sophisticated than prior attempts, but still a FAIL.

As always, I’m happy to share these Excel files for people to look themselves.

We are young, heartache to heartache we stand; No promises, no demands #azvote13

Hashtags are an interesting 21st century phenomenon. Hashtags are keywords to organize information to describe a tweet and aid in searching (Small, 2011). Hashtags also take on a symbolic quality and perhaps are an example of metacommunication. When I post a picture of parents recording every minute of a kids’ holiday concert, complaining about how this is ruining the experience, I can add a hashtag #guilty to metacommunicate that I too participate in this. Symbolic use of hashtags also could be a way to show solidarity with some larger Internet community. When one sees a hashtag on a written sign at a rally, it shows some sort of connection to others that recognize the hashtag.

With that being said, analysis of a hashtag is much easier when there is a time-bound event like a rally or a protest, or in the case of this analysis, an election. When a hashtag is proposed for an event or topic, the intention is for a community of users to share information with each other. But hashtags also serve other purposes during an event: they can promote the event itself (come to the protest! #protest); they can give locationally situated information (the police are at the west gate #protest), and allow for live reporting that may send the message out to sympathetic others or media (Earl, McKee Hurwitz, Mejia Mesinas, Tolan, & Arlotti, 2013; Penney & Dadas, 2013).

For an election event in particular, a hashtag can serve as a means to share information, live report, and also to report possible fraud or violations. In the lead up to an election, a hashtag can be used for information dissemination.

With all that being said, hashtags also serve a boastful purpose. When a hashtag “trends” – it is noted by Twitter as being popular at a particular time. Users want a hashtag to trend to gain visibility and attention (Recuero & Araujo, 2012). While occasionally hashtags trend organically, it is much more common that hashtags are artificially pushed to the trending list (Recuero & Araujo, 2012).

This quantification of social media viability is very attractive. It allows a group to “prove” that it has a lot of support, even if it is artificial.

So, with that being said, let’s have a look at the hashtags for the 2013 Azerbaijani presidential election. (Here’s a pre-election report to give you a sense of the background).

A few different hashtags have emerged in the run up to the election. #azvote13 as well as #azvote2013, #secki2013, #sechki2013, and #besdir (the slogan of the main opposition candidate) are some of the most popular. I’ve been archiving #azvote13 and #secki2013 and #besdir for over a month.

It is important to note that pro-governmental forces have been engaging in some serious hashtag shenanigans all this year – hijacking hashtags thus rendering them useless for organizational purposes, amongst other things. However, in the past month or two, opposition youth have gotten more active on Twitter and seemed to take a stronger hold at different points recently. (Stronger hold = were the largest users of the hashtag.) There were a few alternative hashtags that emerged to make fun of a candidate, but overall the type of behavior that was seen earlier this year seems to have calmed down.

All this hashtag battling seems a little silly to me. But as noted before, hashtags are not just about being an information source, but about sending a signal. Thus, that tagging (to one’s own followers) is showing that “I’m talking about the election.”

Here’s some guidance on understanding these charts. One way to understand who a cluster is is to look at the links that they most frequently share and the source of those links. Are they tweeting from state news sources or opposition news sources, for example?

Here are the hashtags tracked over a long period of time:

#secki2013 – for the last month or so

The largest group of users of this hashtag were not connected to other people. But the second largest group was centered around opposition-leaning Hebib Muntezir (who has long been an information source for Azerbaijani news, lives outside of Azerbaijan, and currently works for an opposition-leaning sat/internet TV channel). Muntenzir’s following is quite interesting – the people around him aren’t heavily linked with each other. And they are receiving information from him, not vice versa – implying that he is an information source rather than a back-and-forth chatter.

Group 3 is the next largest group and it is the pro-government youth. They’re fairly interwoven with each other, and it centers on Rauf Mardiyev, the chairman of IRELI. You can see that his followers, like Muntenzir’s are a little distant from him. He is more a source of information than a chatter.

Group 4 is a very tight cluster – this is all the oppositionists. This is the first time that I’ve seen them all together in a cluster like this. Usually they subdivide into smaller clusters, but with links between them. There is a lot of communication between these people and a lot of efficient information sharing.

Group 5 contains the most active Twitter chatters of the opposition youth. They ended up in their own cluster probably because of how frequently they talk with each other.

#azvote13 – for the last month or so

The largest group here is the pro-government youth organization in Group 1. They’re pretty tight, although you can see some distant subclusters.

Group 2 is all the foreign media and NGOs that was covering the election as well as Azerbaijanis and foreigners that “affiliate” with these organizations.

Group 3 are the non-networked people.

Group 4 are the oppositionists and some media (usually when an opposition leader wrote a piece for a particular news organization and the tweet went out “@soandso’s article at @mediaorg”).

Group 5 is opposition youth – note the ties between group 4 and group 5.

Group 6 is muntenzir’s followers.

So what about election day itself?

#azvote13 for just election day

What’s interesting about election day itself isn’t so much the clusters as the content of what was tweeted – Lots of news coverage from every side. Also many instagram and Facebook photos of people voting, their ballots, and occasionally election violations.

—

So overall, Twitter is a battlefield. What is to be “won” is still not clear to me. I doubt this is a good use of anyone’s time to battle like this, but…

5pm Oct 9 hashtag update

More to come, but…

Group 1, the largest group, was unnetworked people.

Group 2 is a big cluster of foreign organizations and some individuals, Azerbaijani and foreign, associated with them. Seems like it was a lot of discussion and re-tweeting of Rebecca Vincent.

Group 3 is pro-government.

Group 4 is Azerbaijanis associated with the opposition.